News

News

Bringing Global Awareness

And ye shall know the TRUTH, and the Truth shall make you FREE. – John 8:32

My people are destroyed for lack of knowledge: because thou hast rejected knowledge, I will also reject thee. . . – Hosea 4:6

SOVEREIGN NATIONS REFUSING

USA/UNITED NATIONS

KING ALFRED PLAN…

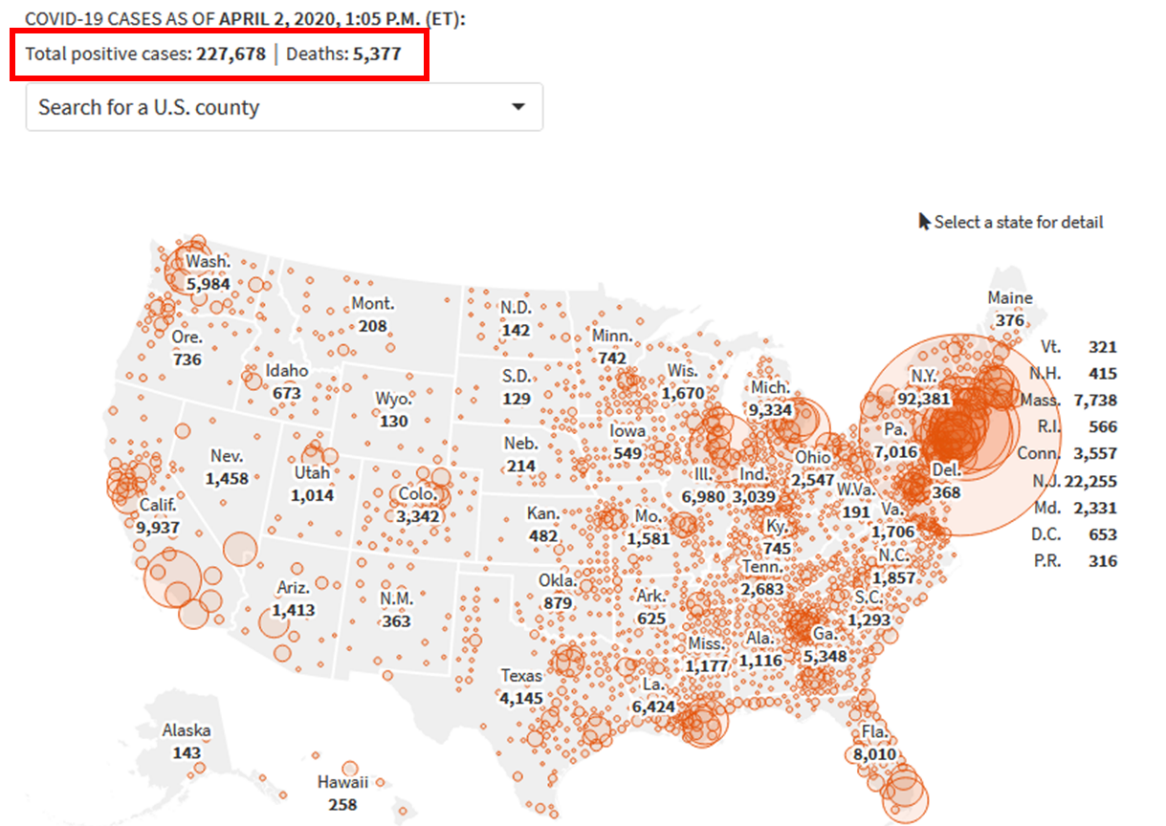

As of 04/02/20: Utica INTERNATIONAL Embassy’s

03/26/20 “STATE OF THE WORLD ADDRESS”

https://youtu.be/WGqKq6ZH9e0 - https://vimeo.com/402740817 - https://login.filesanywhere.com/fs/v.aspx?v=8c6a68875a6776bc719a

As of 03/29/20 Cut and Paste from: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/King_Alfred_Plan

PDF Version of this webpage may be found at:

https://bringingglobalawareness.website/king-alfred-plan-mccarran-act

Pictures added for EMPHASIS

King Alfred Plan

The "King Alfred Plan" is a supposed CIA-led scheme supporting an international effort to eliminate people of African descent,

http://fourwinds10.com/siterun_data/health/vaccinations/news.php?q=1581523652

invented by author John A. Williams in his novel The Man Who Cried I Am. Williams described it as a government plan to deal with the threat of a black uprising in the United States by cordoning off black people into concentration camps in the event of a major racial incident.

Contents

1967 novel

The King Alred Plan first appeared in William's 1967 novel, The Man Who Cried I Am, an account of the life and death of Richard Wright. In the afterword to later editions, Williams compares the King Alfred Plan to intelligence programs devised by J. Edgar Hoover in the 1960s to monitor the movements of black militants.[1]

As of 04/02/20: https://youtu.be/-IOS4h5KMts and/or https://drive.google.com/open?id=1CnUXZbJ7W3bVbVt0ZVszbhg5GAsvl7xB

It also bears similarities to rumors in the early 1950s surrounding the McCarran Act, an anti-Communist law, in which political subversives were to be rounded up and placed in concentrations camps during a national emergency.

When his novel was first published, Williams photocopied portions of the book detailing the King Alfred Plan and left copies in subway car seats around Manhattan.[2]

Cultural dissemination

As a result, word of the King Alfred Plan spread throughout the black community. The truth of its existence was often assumed to be unchallenged.[2] Performer and musician Gil Scott-Heron created the song "King Alfred Plan," included on his 1972 album Free Will, that takes the Plan at face value. Jim Jones, head of the 'apostolic socialist' People's Temple, discussed the Plan at length in numerous recordings of his rant-style speeches both in the USA and in the Jonestown community in Guyana, treating it as completely genuine.

In an interview with Jet Williams explained that he developed the idea when thinking about the question "What would any administration do in a situation when a large segment of the population was discontented and tearing down the neighborhood . . . threatening the order and the established regime?"[3]

References

- Campbell, James (September 9, 2004). "Black American in Paris". The Nation. Archived from the original on 2009-02-12. Retrieved 2020-02-22.

- "Two Celebrated Authors saying Blacks facing genocide in the United States". Jet Magazine. 14 October 1971. Retrieved 3 August 2016.

External links

Emre, Merve (December 31, 2017). "How a Fictional Racist Plot Made the Headlines and Revealed an American Truth". The New Yorker. Retrieved August 14, 2018.

As of 04/02/20: https://www.slideshare.net/VogelDenise/040220-usas-military-population-control-and-concentration-camps-manualmasked and/or https://drive.google.com/open?id=1cOBzzRDJXgPjq216p_VbDkZiBaj9tWDL

McCarran Internal Security Act

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

(Redirected from McCarran Act)

Jump to navigation Jump to search

|

McCarran Internal Security Act |

|

|

|

|

|

Other short titles |

|

|

Long title |

An Act to protect the United States against certain un-American and subversive activities by requiring registration of Communist organizations, and for other purposes. |

|

Nicknames |

Internal Security Act of 1950, Concentration Camp Law |

|

Enacted by |

|

|

Effective |

September 23, 1950 |

|

Citations |

|

|

Public law |

|

|

Codification |

|

|

Titles amended |

|

|

U.S.C. sections created |

50 U.S.C. ch. 23, subch. I § 781 et seq. |

|

Legislative history |

|

|

|

The Internal Security Act of 1950, 64 Stat. 987 (Public Law 81-831), also known as the Subversive Activities Control Act of 1950, the McCarran Act after its principal sponsor Sen. Pat McCarran (D-Nevada), or the Concentration Camp Law,[2] is a United States federal law. Congress enacted it over President Harry Truman's veto.

Contents

- 1 Provisions

- 2 Legislative history

- 3 Constitutionality

- 4 Use by U.S. military

- 5 Fictional reimagining

- 6 See also

- 7 References

- 8 External links

Provisions

Its titles were I: Subversive Activities Control (Subversive Activities Control Act) and II: Emergency Detention (Emergency Detention Act of 1950).[3]

The Act required Communist organizations to register with the United States Attorney General and established the Subversive Activities Control Board to investigate persons suspected of engaging in subversive activities or otherwise promoting the establishment of a "totalitarian dictatorship," either fascist or communist.

Members of these groups could not become citizens and in some cases were prevented from entering or leaving the country. Immigrants found in violation of the act within five years of being naturalized could have their citizenship revoked.

United States Attorney General J. Howard McGrath asked that the Communist Party provide a list of all its members in the United States, as well as 'reveal its financial details'.[4] Furthermore, members of 'Communist-Action Organizations' including those of the Communist Party of the United States of America were required (prior to a 1965 Supreme Court case mentioned below)[5] to register with the U.S. Attorney General their name and address and be subject to the statues applicable to such registrants (e.g. being barred from federal employment, among others).[6] In addition, once registered, members were liable for prosecution solely based on membership under the Smith Act due to the expressed and alleged intent of the organization.[7][8]

The Act also contained an emergency detention statute, giving the President the authority to apprehend and detain "each person as to whom there is a reasonable ground to believe that such person probably will engage in, or probably will conspire with others to engage in, acts of espionage or sabotage."[9]

It tightened alien exclusion and deportation laws and allowed for the detention of dangerous, disloyal, or subversive persons in times of war or "internal security emergency".

The act had implications for thousands of people displaced because of the Second World War. In March 1951, chairman of the United States Displaced Persons Commission was quoted as saying that 100,000 people would be barred from entering the United States that otherwise would have been accepted. By March 1, 1951, the act had excluded 54,000 people of German ethnic origin and 12,000 displaced Russian persons from entering the United States.[10] Notable persons barred from the United States include Ernst Chain, who was declined a visa on two occasions in 1951.[11]

The Act made picketing a federal courthouse a felony[12] if intended to obstruct the court system or influence jurors or other trial participants.[13]

Legislative history

Passage

Several key sections of the Act were taken from the earlier Mundt–Ferguson Communist Registration Bill, which Congress had failed to pass.[14]

It included language that Sen. Mundt had introduced several times before without success aimed at punishing a federal employee from passing information "classified by the President (or by the head of any such department, agency, or corporation with the approval of the President) as affecting the security of the United States" to "any representative of a foreign government or to any officer or member of a Communist organization". He told a Senate hearing that it was a response to what the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) had learned when investigating "the so-called pumpkin papers case, the espionage activities in the Chambers-Hiss case, the Bentley case, and others."[15]

President Harry Truman vetoed it on September 22, 1950, and sent Congress a lengthy veto message in which he criticized specific provisions as "the greatest danger to freedom of speech, press, and assembly since the Alien and Sedition Laws of 1798," a "mockery of the Bill of Rights" and a "long step toward totalitarianism".[16][17]

The House overrode the veto without debate by a vote of 286–48 the same day. The Senate overrode his veto the next day after "a twenty-two hour continuous battle" by a vote of 57–10. Thirty-one Republicans and 26 Democrats voted in favor, while five members of each party opposed it.[18]

Amended

Part of the Act was repealed by the Non-Detention Act of 1971 after facing public opposition, notably from Japanese Americans. President Richard Nixon, while signing the repeal bill, referred to the internment of Japanese Americans during World War II for historical context as to why the bill needed to be repealed.[19]

For example, violation of 50 U.S.C. § 797 (Section 21 of "the Internal Security Act of 1950"), which concerns security of military bases and other sensitive installations, may be punishable by a prison term of up to one year.[20]

The part of the act codified as 50 U.S.C. § 798 has been repealed in its entirety for violating the First Amendment.[21]

Abolition

The Subversive Activities Control Board was abolished by Congress in 1972.[22]

Constitutionality

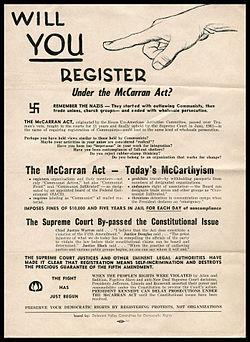

Civil libertarians and radical political activists considered the McCarran Act to be a dangerous and unconstitutional infringement of political liberty, as exemplified in this 1961 poster.

The Supreme Court of the United States was initially deferential towards the Internal Security Act. For example, in Galvan v. Press,[23] the Court upheld the deportation of a Mexican alien on the basis that he had briefly been a member of the Communist Party from 1944 to 1946, even though such membership had been lawful at that time (and had been declared retroactively illegal by the Act).

As McCarthyism faded into history, the Court adopted a more skeptical approach towards the Act. The 1964 decision in Aptheker v. Secretary of State ruled unconstitutional Section 6, which prevented any member of a communist party from using or obtaining a passport. In 1965, the Court voted 8–0 in Albertson v. Subversive Activities Control Board to invalidate the Act's requirement that members of the Communist Party were to register with the government. It held that the information which party members were required to submit could form the basis of their prosecution for being party members, which was then a crime, and therefore deprived them of their Fifth Amendment right against self-incrimination.[24] In 1967, the act's provision prohibiting communists from working for the federal government or at defense facility was also struck down by the Supreme Court as a violation of the First Amendment's right to freedom of association in United States v. Robel.[25]

Use by U.S. military

The U.S. military continues to use 50 U.S.C. § 797, citing it in U.S. Army regulation AR 190–11 in support of allowing installation commanders to regulate privately owned weapons on army installations. An Army message known as an ALARACT[26] states "senior commanders have specific authority to regulate privately owned weapons, explosives, and ammunition on army installations." The ALARACT refers to AR 190-11 and public law (section 1062 of Public Law 111–383, also known as the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2011); AR 190–11 in turn cites the McCarran Internal Security Act (codified as 50 USC 797). The ALARACT reference is a truncated version of the public law.[27]

Fictional reimagining

The 1971 pseudo documentary film Punishment Park speculated what might have happened if Richard Nixon had enforced the McCarran Act against members of the anti-war movement, black power movement, the feminist movement, and others.

See also

- Alien Registration Act

- Espionage Act of 1917

- Hatch Act of 1939

- Mundt-Nixon Bill of 1948

- Mundt–Ferguson Communist Registration Bill of 1950

- National Committee to Defeat the Mundt Bill (1948-1950)

- McCarran–Walter Act

- McCarthyism

References

Izumi, Masum (May 2005). "Prohibiting "American Concentration Camps"". Pacific Historical Review. 74 (2): 165–166. doi:10.1525/phr.2005.74.2.165. JSTOR10.1525/phr.2005.74.2.165.

The Full Text of the McCarran Internal Security Act, accessed June 25, 2012

Wood, Lewis (1950). "Russia Dominates US Reds, McGrath Formally Charges". The New York Times. ProQuest111584130.

Albertson v. Subversive Activities Control Board

Title I, Section 5-7

Smith Act trials of Communist Party leaders

Title II, Section 103

"Gibson Holds Law Bars 100,000 D.P.'s". The New York Times. March 10, 1951. ProQuest111830215.

"No Admission". The New York Times. December 9, 1951. ProQuest111905452.

New York Times: "M'Grath to Press New Curbs on Reds," September 25, 1950, accessed June 25, 2012

Title I, Section 31

Everything2: The Nixon-Mundt Bill Retrieved 2012-04-10

Justia: Scarbeck v. U.S. paragraphs 20-1, accessed June 25, 2012

Harry S. Truman, Veto of the Internal Security Bill, Harry S. Truman Library and Museum.

"Text of President's Veto Message Vetoing the Communist-Control Bill" (PDF). New York Times. September 23, 1950. Retrieved April 23, 2013.

Trussel, C.P. (September 24, 1950). "Red Bill Veto Beaten, 57-10, By Senators" (PDF). New York Times. Retrieved April 23, 2013.

Izumi, Masumi (May 2005). "Prohibiting "American Concentration Camps"". Pacific Historical Review. 74 (2): 166. doi:10.1525/phr.2005.74.2.165. JSTOR10.1525/phr.2005.74.2.165.

United States Department of Defense DoD Directive 5200.8, "Security of DoD Installations and Resources", 25 April 1991, retrieved August 26, 2005. Archived July 9, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

"50 USC 798". Findlaw.

(PDF) http://cisupa.proquest.com/ksc_assets/catalog/10837.pdf. Missing or empty |title= (help)

Galvan v. Press, 347 U.S. 522 (1954),

Belknap, Michael R. (2004). The Vinson Court: Justices, Rulings, and Legacy. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO. p. 171. ISBN9781576072011.

Belknap, Michael R. (2005). The Supreme Court Under Earl Warren, 1953-1969. University of South Carolina. p. 79. ISBN9781570035630.

ALARACT 333/2011 DTG R 311939Z AUG 11

Public Law. "111-383" (PDF). section 1062. 111th Congress.

External links

- The Full Text of the McCarran Internal Security Act

- Department of Defense Instruction, December 2005 (from Defense Technical Information Center)

News

News

Bringing Global Awareness News seeks to enlighten the Global accomplishments of “UNIFIED” Native Nations and their People that the Public / World may not see in the European – controlled / White Man’s Mainstream Media! Furthermore, provides information regarding the MAJOR roles of Native Nations to TAKE BACK their Lands / Territories from the unlawful European Occupations . . . around the World!

Contact Information:

Mailing Address:

Bringing Global Awareness News

c/o Prime Minister Vogel Denise Newsome

Post Office Box 31265

Jackson, Mississippi 39286

Phone: (888) 700-5056 (Extension 8000)

Email: bganews@bringingglobalawareness.website